Coroutines As Threads

This post is part of the blogpost series explaining coroutines, how they implemented in various programming languages and how they can make your life better:

The main motivation for these blogposts is that, probably like many other developers, I heard about coroutines, continuations, yield/async/await and even used them to some extent, but I never got to really understand what they mean from computational point of view, how they work and how concepts like continuations relate to coroutines. This is an attempt to clarify coroutines for myself and anyone else interested in the subject.

The classification of coroutines as threads, yield/async/await and call/cc is my own attempt to identify commonalities between languages. To draw analogy with design patterns, quite a few behavioural patterns are at their core based on dynamic dispatch. Each pattern adds more details on top of dynamic dispatch to solve a particular problem but fundamentally they all rely on dynamic dispatch. Similarly, coroutines have implementation specific details but they all could be explained with the same core idea of saving current stack and execution pointer and later using this information to continue execution from suspension point.

Why use coroutines?

There are multiple reasons you might want to use coroutines. They will be explained in more details in later posts but here is a quick description of few main use-cases:

-

Concurrency in single-threaded environment. Some programming languages/environments have only a single thread. This might be done by design (e.g. in Lua and JavaScript) because it simplifies a lot of things in the language. In other languages like Python, you can have multiple threads but because of global interpreter lock they cannot be used concurrently. Another example is an embedded device running an OS without threads. In all these cases, if you need concurrency, coroutines are your only choice.

-

To simplify code. It can be done by using

yieldkeyword to write lazy iterables, by usingasync/awaitto “flatten” asynchronous code avoiding callback hell or by writing asynchronous code in imperative style (and staying away from converting all the code into pure functional style, e.g. see this blog post). -

Efficient use of OS resources and hardware. If the design of your application requires a lot of threads, then you can benefit from coroutines by saving on memory allocation, time it takes to do context switching and ultimately benefit from using hardware more efficiently. For example, if each “business object” in your application is assigned a thread, then by using coroutines you will need less memory and will benefit from faster context switching between coroutines. Another example is using non-blocking IO with many concurrent users. Because in general, threads are more expensive than sockets, you will run out of available OS threads faster than sockets. To avoid this problem you can use non-blocking IO with coroutines.

Brief history

There is nothing new about coroutines from computer science point of view. According to wikipedia coroutines were known as early as 1958. There were implemented in high-level programming languages starting with Simula 67 and Scheme in 1972. Coroutines were so old news by the 90s that John Reynolds wrote The Discoveries of Continuations paper in 1993 describing the rediscoveries of continuations. Until about the 80s there were no threads easily available in operating systems so if you needed any concurrent behaviour you would have to use coroutines or something similar. Later on, when threads became widespread, it seems that everyone forgot about coroutines for a while. Until recently, when coroutines came back into the mainstream.

Coroutine definition

A coroutine is a function which:

- can suspend its execution (the expression where it suspends is called suspension point);

- can be resumed from suspension point (keeping its original arguments and local variables).

This is an informal definition because there seems to be no consensus about what exactly “coroutine” means. There are few ways in which coroutines are implemented in programming languages. The most widespread implementations are coroutines as threads, yield/async/await and “call/cc” (which stands for “call with current continuation”). Under the hood they all use the same idea, so it might be useful to think about them as design patterns which use the same underlying mechanism to solve different problems.

Coroutines as threads

Lua is a scripting programming language designed to be used as an embedded language in large applications (thinking about it as “javascript for interacting with C” might be a fair analogy). In case you never encountered Lua, it is the most used scripting language in the gaming industry and definitely falls into the category of industrial strength enterprise languages.

Lua is good for the purpose because it has quite typical implementation of coroutines as threads and has straightforward syntax which should be readable for most people.

Notation

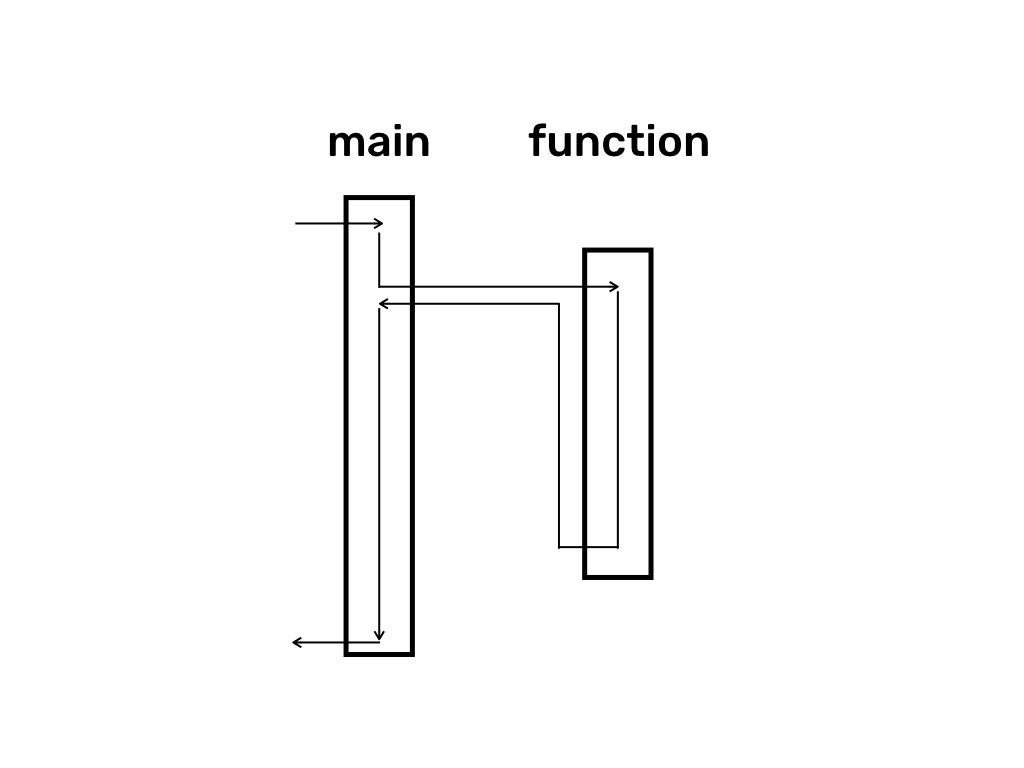

In order to illustrate coroutines, I will use the following graphical notation:

In this notation, rectangles represent functions as a sequence of instructions executed from the top to the bottom. Solid lines represent threads with arrows showing direction in which the thread executes instructions. For example, in the diagram above a thread starts executing program’s main function, at some point it calls function, executes it, returns back to the execution point in main, finishes main and terminates the whole program (main here represents program’s entry point named after “main” function in C).

An equivalent code in Lua which prints hello, executes sub-function to print from, then returns to main and prints Lua, looks like this:

Basic coroutine

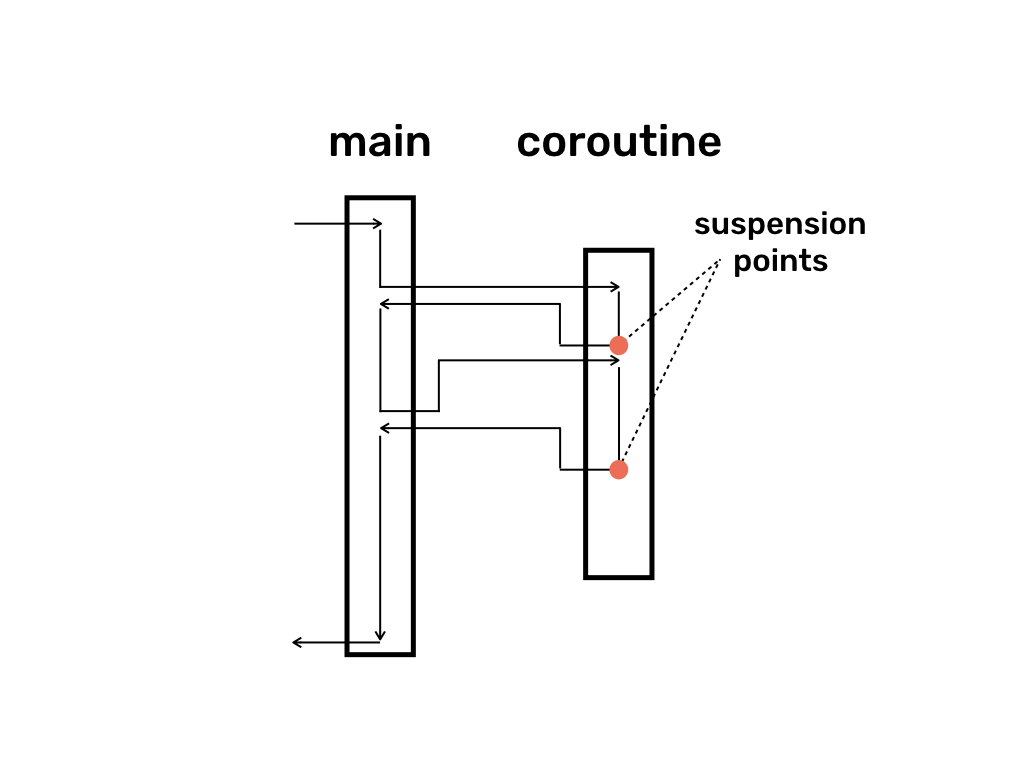

Now here is a diagram representing execution of a basic coroutine:

In the diagram some thread enters main, executes a bit of code and invokes the coroutine. Coroutine executes few instructions until it reaches suspension point which saves current stack and instruction pointer somewhere in memory. (In this context “stack” and “instruction pointer” are used in an abstract way and don’t necessarily imply any particular implementation. They are used as a convenient way to think about what’s going on.) After the suspension point the coroutine returns back to main just like a normal sub-function. Some time later, after executing a bit of code, main calls the coroutine again. Coroutine starts executing from the last suspension point, i.e. effectively it restores saved stack and jumps back to the saved instruction pointer. After executing a few more commands the coroutine reaches another suspension point which saves the current stack and instruction pointer again and returns back to main. After this main executes a few more commands and the whole program terminates. (As you have probably noticed, the coroutine didn’t fully finish execution before finishing main.)

Below is the equivalent code in Lua:

First of all, we define coroutine with the coroutine.create library function by passing an anonymous function as an argument. After assigning the coroutine to variable c, main prints 1 and starts the coroutine with the coroutine.resume function. The coroutine prints 2 and calls another library function coroutine.yield which acts as a suspension point, i.e. saves stack and instruction pointer of the coroutine and returns to main. After this main prints 3, resumes coroutine again which prints 4 and yields back to main one more time. Overall, the program prints 12345 and never reaches the line to print monkey (similar to the diagram above which never finishes execution of coroutine). Note that we can only call coroutine.yield from the coroutine body. If we attempt to do it from the main, the code will fail at runtime with “attempt to yield from outside a coroutine” error.

Coroutine status

Similar to threads, coroutines can have status. In the example below we create a coroutine but instead of printing numbers we print the result of coroutine.status(c) which, as you can guess, returns the status of coroutine c. This example will print status suspended when invoked in main and running when in coroutine c. After the coroutine executes all the commands, it ends up with the dead status. This mimics the status of threads given that they can only be executed one at a time. (In case you were wondering, in Lua .. is a string concatenation operator similar to + in most C-like languages.)

Send/receive values from coroutines

Coroutines in Lua can send/receive values at suspension points (admittedly, in this case analogy with threads doesn’t work that well).

In the code above we create coroutine as usual with coroutine.create function but unlike the previous examples we pass one more argument to coroutine.resume. Initially, we pass 1 so when the coroutine starts, n has a value of 1. Coroutine prints 1 and yields it’s execution returning 2. In the main the expression coroutine.resume(c, 1) evaluates as 2 by getting yielded value from the coroutine and assigns it to variable m (in this example _ is part of multi-assignment and can contain an error message). Overall, the program will print the following:

c received: 1

main received: 2

c received: 3

main received: 4

c received: 5

All functions as coroutines

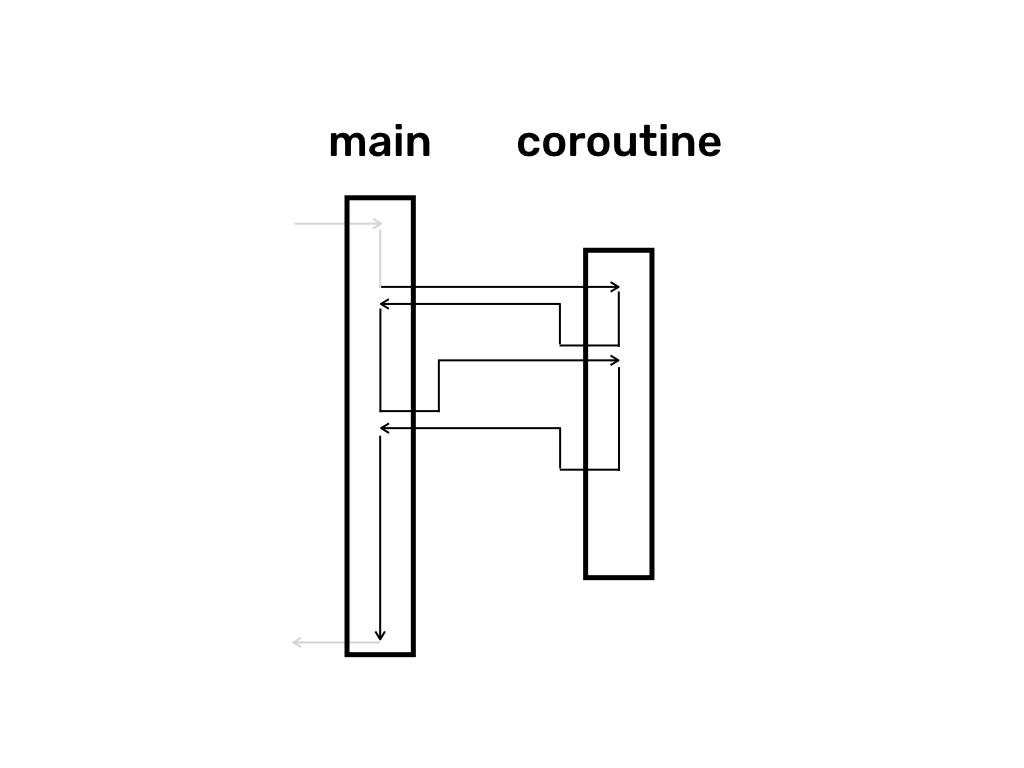

In the diagram below, if you ignore entry and exit points into the main function, then the whole invocation sequence looks quite symmetric. There seems to be no big difference between main and coroutine as if they are just two threads switching execution between each other.

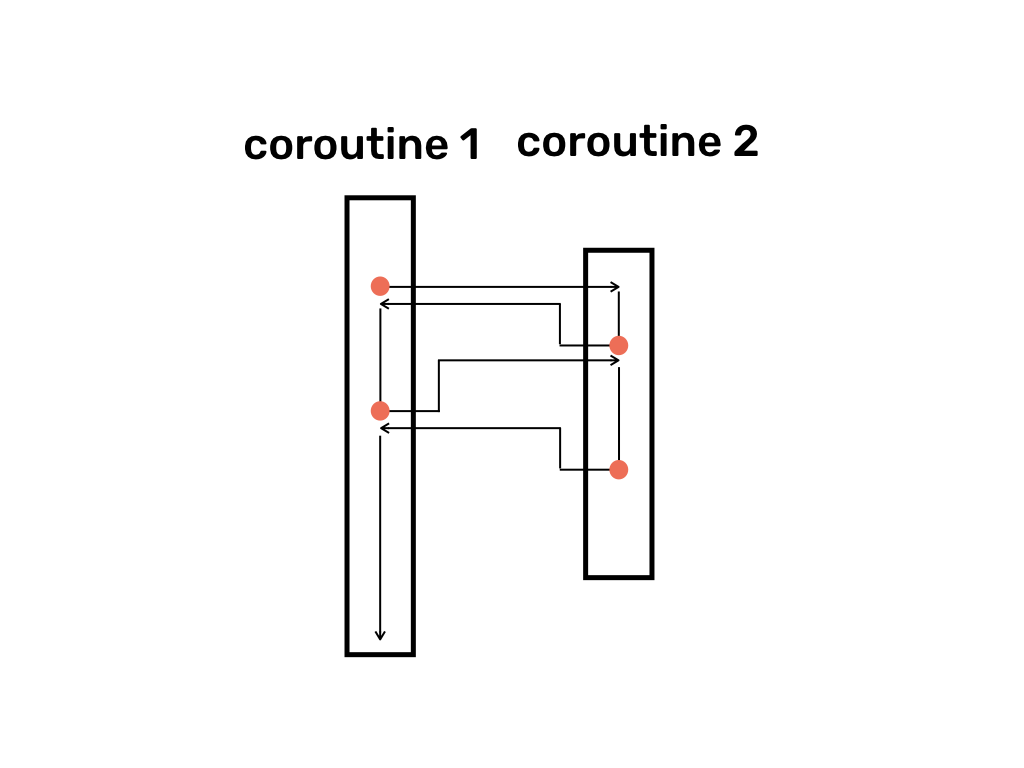

So we could rename main and coroutine to coroutine 1 and coroutine 2.

And, in fact, there is a way to write code with the same functionality using two coroutines. In the following example main function resumes coroutine c1 which resumes coroutine c2, and then coroutines switch between each other similar to the diagram above.

This is the most basic example of how to achieve concurrency in a single-threaded environment by using cooperative multitasking which is one of the main reasons to use coroutines as mentioned in the beginning of this blogpost. If you imagine that coroutine.yield and coroutine.resume are automatically sprinkled over the coroutines by some other program which we could call “scheduler”, then we no longer control context switching between coroutines and it becomes preemptive multitasking. Arguably, this is the point when we can no longer say that we are dealing with coroutines.

Stackful vs stackless coroutines

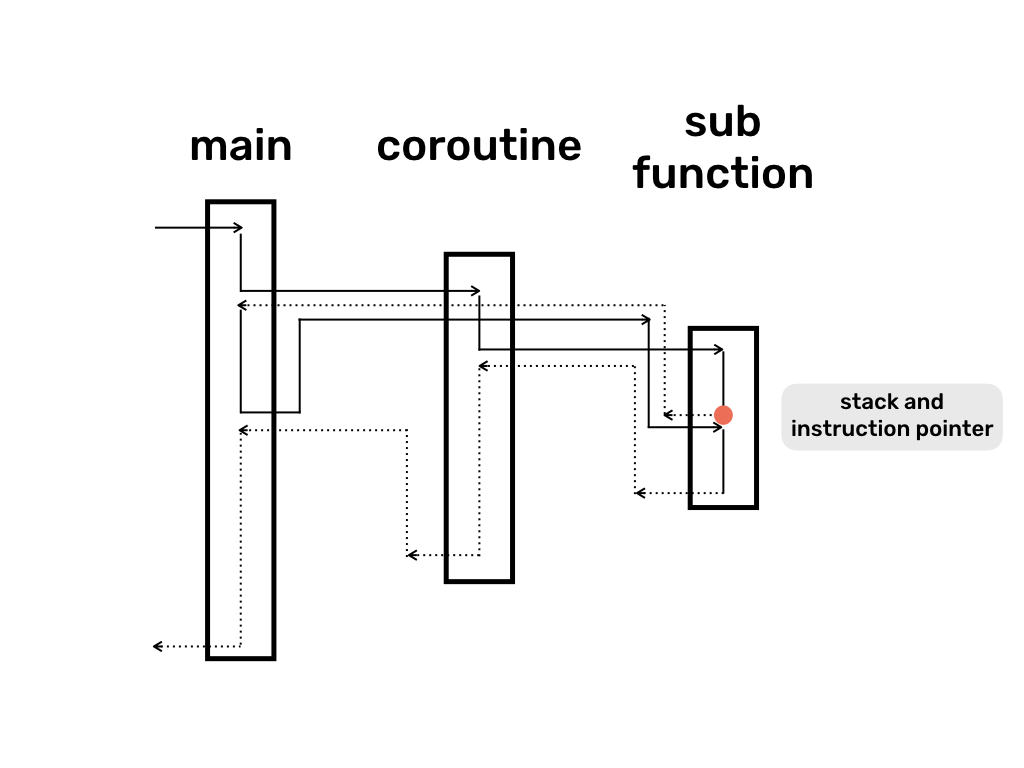

The final thing worth mentioning in the context of coroutines as threads, is the ability of coroutines to yield execution from sub-functions. For example, in the diagram below main invokes coroutine which in its turn invokes a sub-function. (The dotted lines in the diagram have the same meaning as solid lines. The only reason for dotted lines is to make the diagram less cluttered.)

When sub-function reaches the suspension point, it returns back all the way into the main function. After that, main executes some more code and resumes the coroutine. When resumed, the coroutine continues execution directly from the suspension point in sub-function, which when finished returns normally to the coroutine and to main. If you think about main as one thread and coroutine with sub-function as another thread, then this is a perfectly reasonable behaviour because when threads switch execution between each other it doesn’t matter if one of the threads is currently in the middle of some sub-function.

Coroutines implementations which are capable of yielding from sub-functions are called stackful, i.e. they can remember the whole invocation stack. Other implementations of coroutines, which can only yield execution from the top level of coroutine function, are stackless. Lua implementation of coroutines is stackful so we can write code like in the example below, which outputs 1234567.

Summary

There are few terms related to the idea of coroutines being used as threads: fibers, green threads, protothreads and goroutines. They all mean similar things but the encompassing theme is to not use OS threads for concurrency or multitasking. The reason might be that the OS or programming environment doesn’t support threads at all or that it’s more efficient to use custom context switching mechanism. There is no specific requirement, however, that there is only one OS thread or CPU executing coroutines and particular implementation can be using multiple threads, but this is implementation details.

Overall, thinking about coroutines as lightweight threads is the most intuitive and the most high-level metaphor for coroutines. Compared to actual threads the biggest conceptual difference is the lack of scheduler (all context switching must be done by the program) and the fact that coroutine implementations can be stackless.

Read next: yielding generators.